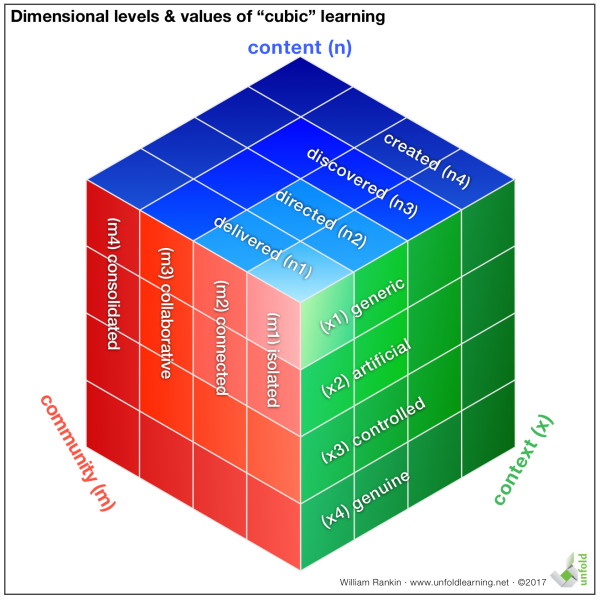

In my last post, I described the ways the “cubic” model could be used to evaluate learning approaches and described a method for calculating “engagement and learning multiplier” (ELM) scores. If you aren’t familiar with these concepts, you might want to review that post before continuing…

Over the next several posts, I’ll perform cubic ELM assessments of several common learning approaches. For each, I’ll set the learning scenario and then present analysis about why that approach has a given “cubic” shape and why it receives a particular ELM score. Hopefully, these posts will provide useful examples and guidance as you evaluate your own learning approaches and as you make your own teaching and technology choices.

A traditional lecture course

Description

In this course, the teacher presents information most days through a combination of lectures and presentations — some conducted using an “interactive” white board. The teacher also incorporates materials from the course textbook in her lectures, highlighting the points learners will have to know for exams. Learners are expected to take careful notes, and exams and other assessments come largely from material the teacher has covered in lecture, though some also comes from exercises and readings in the course text. During class, learners are encouraged to ask questions if they don’t understand a concept, and the teacher organizes weekly discussions where she probes learners’ understanding of course topics. In addition to homework exercises, learners are expected to complete a major research project. This project is designed to introduce learners to important books and journals in the discipline, and they must use materials from the school’s library, including the library’s online, full-text database, to complete it successfully. Learners choose from a list of topics furnished by the teacher, who has ensured that library holdings are adequate to support each topic. Assessment of these projects (as with exams and homework) is completed by the teacher, who writes comments designed to correct errors, to help learners acquire disciplinary literacies and conform to disciplinary norms, and to praise particularly insightful or advanced responses. The teacher periodically presents exceptional or noteworthy homework exercises, exam responses, and final projects to the class, being careful to protect the authors’ anonymity, in order to encourage dedicated, thoughtful work. She makes herself readily available outside of class to discuss course concepts and encourages learners to come by her office or contact her by email if they have questions or difficulties. Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.