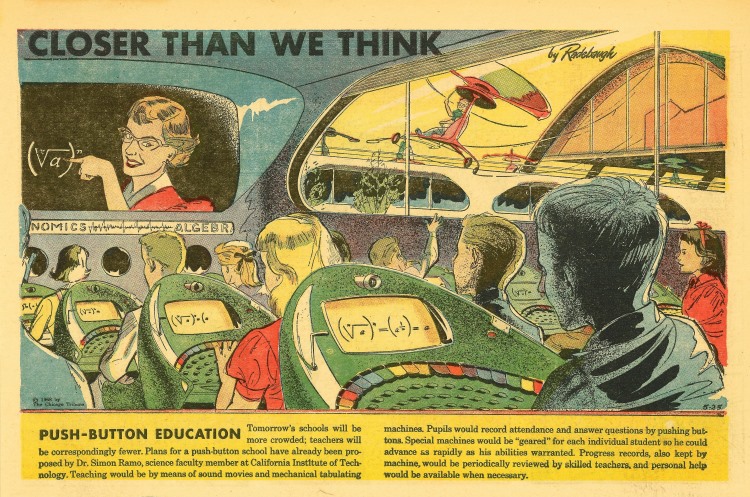

Arthur Radebaugh. “Closer than we think.” 1958. Tribune Media Services, Inc.

Part 1: There and Back Again

Get any group of educators together, and the topic will inevitably turn to “what’s wrong” with our profession. Conference schedules are packed with people lending their voices to the chorus of critiques, and they’re just as packed with people offering this or that “solution” that will magically transform everything — at least until the Next Big Thing comes along.

This is nothing new. In fact, it’s the one constant that has characterized the profession since I started teaching almost 30 years ago. And that’s part of the problem. There’s been such a string of promises — MOOCs, tablets, lightweight web clients, and interactive white boards, to name just a few recent ones — that, despite a few positive-use cases, have all fallen flat. This makes many of us understandably dubious. With all of these broken promises, it doesn’t take long for people in our profession to become jaded, even disinterested. So how do we genuinely move forward without chasing once again after futures that prove illusory?

In this series of articles, I want to explore and provide a theoretical background that can help ground our discussion, giving us a metric for assessing what’s being offered and hopefully helping us avoid some of the false paths we’ve taken in the past. To do so, we need first to think not just about what this or that approach might mean for education but to think about what we mean by words like “good” and “education” in the first place. Going back to such definitions may seem unnecessarily rudimentary, a journey back to origins that everybody already knows. But I’m convinced that it’s our assumption that we’ve all come from the same place — that we all started on the same page — that’s behind many of our conflicts about what education needs next. Without such a shared understanding, it’s far too easy for us to get trapped in blind alleys or dead ends — even if the path we took to get there initially seemed promising and even if lots of other people were with us along the way.

So in this series, I want to ask a few essential questions: what do we mean by education? What tools can we use to differentiate good practice from bad, and what do we mean by “good” and “bad” in the first place? How can our development of an overall metric help our practice move further and how can it restrict us and keep us from discovering new possibilities and innovation? And most importantly, how can our own growth and learning engender the learning we want for our students and make a positive impact in the world?

This last question is one that I care about profoundly. In fact, it’s at the core of my definition of learning. Critically, learning for me is not primarily about the transfer of information, though such transfers often occur in learning situations. Rather, learning is about relating more closely with the world and with the people around us. In terms of information, true learning requires the application of that information in either a relevant context — a situation that gives meaning to the information — or in connection with a relevant community — people who also give meaning to the information. Indeed, true learning typically involves both of these contextual and communal factors.

This model of learning might seem odd for someone who has spent most of his career studying medieval literature. After all, what could be more esoteric than the odd dialects and cultural scraps of people who have been dead for a thousand years? How could any of that connect with our experience of the world today or of its people? But that’s just it. The value of my studies hasn’t resided in any sort of esoteric abstraction; rather, it’s been valuable precisely because it has let me see the world and people around me more clearly — sometimes by contrast, but mostly because I realize that what it means to be human hasn’t changed. Our humor, our worry, our love, these are all instantly recognizable, even if they’re packaged in languages that no lips have uttered for a millennium.

So by way of a beginning to this series, here’s a manifesto: the five natures of learning:

- Learning is connective. It doesn’t exist in tidy packages, but is only recognizable in complex webs of interaction with others and with the world.

- Learning is living. If it doesn’t integrate with our regular experience of the world and grow with that experience, it isn’t real.

- Learning is generative. It gathers, it remixes, it synthesizes, it creates.

- Learning is directive. It sets us on paths — sometimes recursive, sometimes quotidian, sometimes surprising. It doesn’t let us sit still.

- Learning is human. By nature, humans are obsessed with learning, and learning makes us more human. However, if we remove it from real contexts and connections, we can alter, or even defeat, this basic human instinct.

In the next installment, I’ll explore the notion that learning has to be connected to real-world contexts and communities. What constitutes the “real” and why (and how) did education begin to split learning into information disconnected from these two essential elements of meaning-making?

You must be logged in to post a comment.