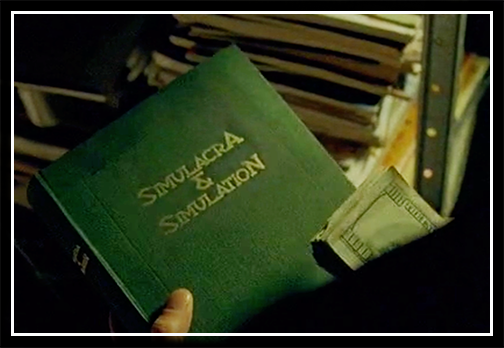

Buadrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation in a still from The Matrix, distributed by Warner Bros., 1999.

Part 2: Simulacra and Simulation

In his 1981 Simulacra and Simulation (print or PDF), the theorist Jean Baudrillard offers a critical framework for understanding how our concept of the world has changed over time, and this can be a useful starting point for thinking about how educational systems and structures are also changing. In this book, Baudrillard’s overall model derives from the production of goods, tracing the changes from small guild workshops to the most mechanized factories. While that may seem irrelevant for discussing trends in education, it actually points to a fascinating parallel: throughout history, we’ve constructed schools and shaped our ideas about learning to mirror the ways we produce objects. Many writers — most recently, Todd Rose in his fascinating The End of Average (digital and print) — have traced the ways that industrialism and factory culture changed the practice of teachers and the expectations for learners, but Baudrillard gives us a longer view and offers us an explanation for why we’ve made the changes we have.

Semioticians like Baudrillard study how we construct meaning through the creation of signs. When we connect meaning (semioticians call this the “signified”) to an object (the “signifier”), we create a “sign,” and signs dictate how we understand and interact with the world. For example, when most of us see a red octagon, we know it means “stop.” The red octagon is the signifier, and the meaning we associate with it, “stop,” is the signified. Yet there’s nothing inherent in red octagons (or even in either just the color red or just octagonal shapes) that would automatically make us think “stop” — at least if we hadn’t already been introduced to the notion of stop signs. Instead, at some point, somebody connected these physical characteristics to this meaning, and in so doing, made a sign — quite literally, in this case. The rest of us agreed (perhaps not overtly, but at least in our practice) to “read” such signs in this manner, and thus whenever we see a red octagon while we’re driving, we stop.

However, in Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard is thinking about more than just the creation of individual signs; he’s thinking about how we make meaning systematically — how we build whole superstructures of meaning. Baudrillard calls these systems of signification “simulations,” and he argues that we’ve experienced 4 major periods of simulation in history. Just as with individual signs, these symbolic superstructures have dictated how we interact with and understand the world around us — and they have much to offer as we consider where education is heading.

Here are the four phases of simulation Baudrillard describes. As you consider each of them, pay special attention to the changes he traces in the relationship between reality and its connection with symbolic meaning. And be forewarned: this gets pretty abstract and philosophical. Nonetheless, it’s critical to lay this foundation so we can build the rest of the articles in this series…

1st-order simulation: This period of human history exists prior to the industrial revolution that began in the 18th Century. At this stage, there was a direct correlation between the meaning we assigned to a thing (the “symbolic”) and the reality it represented. A chair made at this time, for example, was the work of a particular craftsperson who invested a quantifiable amount of time, work, and expertise in making each chair. And every chair — the first or the fiftieth — that came out of a workshop represented the same level of investment. There was no way to speed up or streamline the process because every chair had to be made individually and by hand: making four sets of chair parts simply took four times longer. Because of this direct correlation between the the chair and the symbolic significance it represented (the investment of time, work, and expertise), anyone looking at a chair could quickly recognize and “read” its meaning. In other words, chairs became a kind of sign in which the signifier and the signified were inherently — or even “naturally” — linked. In this phase, one could therefore say that signifiers directly embodied the meaning they conveyed. For Baudrillard, such signs are a “reflection of a profound reality” (6), creating what he refers to as the “sacramental order” of representation.

2nd-order simulation: This period of human history coincides with the early industrial revolution — roughly comprising the 18th to the mid-19th centuries. At this stage, symbolic meaning begins to be diffused or fragmented, and its relationship with reality becomes more tenuous. In this scenario, a chair would still be designed and made by a skilled craftsperson. However, that chair would then be taken as a “model” according to which a number of duplicate chairs could be manufactured — and this could be done even without the consent of the original craftsperson. Indeed, the secret that this second phase hides is that it is seeking to supplant the first phase, manufactured chairs working to replace the old-fashioned, hand-made chairs that served as their models. In this phase, the direct connection between the chair (the “signifier”) and the investment of time, work, and expertise (the “signified”) is sacrificed for productivity and efficiency. The hand-made chair is disassembled and broken down into its constituent parts, and machines are set up to manufacture those parts. But in so doing, corners have to be cut, craft has to be approximated, and the careful attention to individual detail has to be abandoned. Although multiple chairs can now roll rapidly off the assembly line and be distributed and sold to many more people, each manufactured chair contains only a fragment of the “meaning” that first-order chairs carried. Here’s another way to think about it: although the machine operators can crank out many more chairs than the original craftsperson, and although chairs can be manufactured much more rapidly, each factory worker can only accomplish part of the task, and none possesses all of the skills possessed by the original craftsperson. Indeed, such broad-based skills are unnecessary in the factory environment — at best a distraction and at worst, a threat to the factory’s methods. The “signified” that characterized the first phase is therefore now diffused among all of the factory-made chairs, so each “signifier” becomes less powerful, less “real.” Baudrillard concludes that in this second phase, the sign “masks and denatures a profound reality” (6), characterizing such displacement and fragmentation as “the order of maleficence.”

3rd-order simulation: This period coincides with the apex of the industrial age, comprising the mid-19th through the later-20th centuries. At this stage, the notion of manufacturing has become so dominant and so conventional that it has almost entirely displaced the notion of craft, which is seen by most people as quaint and inefficient. But something else has happened in the widespread embracing of mechanization: objects are created not initially for their beauty or quality, or even in many cases for their genuine utility. Rather, they’re created from their very first prototype for their ease of manufacture. It’s like those fruits and vegetables that are grown primarily for their ability to be shipped long distances rather than for their flavor or nutritional value (I’m looking at you, store-bought tomatoes!). What drives consumption now is not necessarily need, but rather marketing and advertising. In this phase, we’re left with a “product” designed from its initial conception to fill a “market” that is just as manufactured as the product itself. And since even the “need” is manufactured, designed and sold by marketers who will obsolesce it for a newly manufactured “need” when the next product comes churning off the assembly line, the tenuous relationship between reality and signification is almost completely severed. Prototypes exist, but they’re conceived and built from the beginning to accommodate only those characteristics that the factory can copy and the marketers want. Product backgrounds and spokespeople are fabricated to fit given market segments. Blue jeans are made not only pre-faded, but pre-worn and pre-torn — even as “fashion” convinces us to toss last year’s perfectly good pair before it has a chance to show the true effects of wear. The world of the third order is thus filled with objects whose every characteristic and rationale are already shaped by the factory’s ability to manufacture them. Not only is there no longer an “original” object tightly connected to human capability and artistry, then, but even the purpose for these objects is becoming divorced from the “real.” In fact, this endless echo-effect becomes so pervasive that people begin to lose touch with what “real” even means — at least in first-order terms. The closest most people get is the ghost of the “real” that still haunts people’s imaginations in the form of nostalgia — efforts that try to borrow the language or the feeling of the first two orders to sell the products of the third. The real world — the notion of human capability and craft — gets a vague nod from marketers and advertisers who claim “home-made flavor” or “crafted with care” for their factory-conceived and -produced products. Yet as meager as this kind of connection to the real is, as diffused and smeared throughout the whole range of clinically or even robotically produced products, the real hasn’t been fully abandoned. Baudrillard calls this third phase “the order of sorcery” in which the symbolic only “plays at being an appearance” (6) — seeking to comfort us with a reassuring “reality,” but one that proves itself almost entirely illusory if we peek behind the curtain. Images in this third phase therefore cover over the fact that there is nothing real behind them because their chief function is to “mask[…] the absence of a profound reality” (6).

4th-order simulation: Baudrillard calls this final phase the “simulacrum.” In this phase, the connection between the symbolic and the real dissolves entirely and what we get is merely an endless array of reflections, a perverse fun-house hall of mirrors in which we see nothing genuine. In this final stage, not only is there no longer a chair created by a skilled and dedicated craftsperson, but even the prototype has disappeared, replaced by a digital file designed to let engineers work out every last detail without ever having to spend a single moment (or a single dollar) on the real world. In this world, the first chair to roll off the assembly line is already a copy, indistinguishable from all of the other copies that will come after it. It hasn’t been adapted from a model because no model ever existed in the real world — only in the ephemeral digital world — and it can only be compared to other objects that, just like it, are always already copies. Indeed, in this sense, it is utterly divorced from what people once considered reality — that connection to human time, work, and expertise. This is the world of the virtual, the world of what Baudrillard calls the “hyperreal,” a world of echoes that cannot be traced back to their original sound because no original exists. In this world,

“The real is produced from miniaturized cells, matrices, and memory banks, models of control — and it can be reproduced an indefinite number of times from these. It no longer needs to be rational, because it no longer measures itself against either an ideal or negative instance. It is no longer anything but operational. In fact, it is no longer really the real […]. It is a hyperreal, produced from a radiating synthesis of combinatory models in a hyperspace without atmosphere.” (2)

In this phase, the image “has no relation to any reality whatsoever; it is its own pure simulacrum” (6).

So to recap, in the first order, things are what they seem because they stay tightly connected to human meaning. In the second order, things pretend to be something they’re not, and they have to pretend because they’re being distanced from human meaning and capability to allow for mechanization and manufacturing. In the third order, things only play at pretending because even mechanization and manufacturing are being displaced by marketing — the fabricated connection to human meaning and capability through a kind of fictional nostalgia. In the fourth order, things are no longer connected to genuine meaning and become only virtual and self-referential, a world of disconnected echoes. Because their origins are purely digital and because the digital is ephemeral, easily changed or erased, they no longer have any significant connection to the real.

It’s a pretty bleak picture and one that may be surprising for those of us who are deeply invested in the digital world. But whether you buy Baudrillard’s model or not, this progression offers us an opportunity not only to understand the present condition of our educational system, but also to plot its future trajectory — and to change it if we wish. This article and the next will trace some of the ways Baudrillard’s theories apply, and that will open the door for later installments in this series where we’ll consider how to move beyond where we find education today.

For now, let’s consider the parallel series of phases that we can trace through educational history, a “four orders of learning” that roughly matches the time periods and characteristics of Baudrillard’s four orders. Seen through the lens of Baudrillard’s theory, the history of learning looks something like this:

1st-order learning: This model was dominated by a holistic focus centered around human craft. Teaching and learning were practiced in small, highly personalized contexts — the guild, the family, the mentor/disciple relationship. Some schools formed in this period, notably Oxford and Cambridge Universities, still structure much of their teaching and learning around these close, highly interactive relationships. In this stage, teachers worked to guide students by giving them tailored assignments that matched students’ individual capabilities (Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria provides an excellent discussion), and students’ progress was measured largely by their ability to make or perform in real-world contexts. Assessment was conducted not only by an individual teacher or guide, but often by a related group or guild — or even by the community at large. However, learning progress had not yet been abstracted into grades or scores, so there was no way to speed up or streamline the educational process since every learner had to be prepared and evaluated individually. Each learner proceeding through this system thus represented the same level of investment on the part of the teacher or guide. Because of this direct correlation between the learners and the symbolic significance their learning represented (the investment of time, work, and expertise), anyone could quickly recognize the “meaning” of their learning. In other words, being “learned” became a kind of sign in which the signifier and the signified were inherently — or even “naturally” — linked. Further, even abstract or philosophical studies were grounded in the real both through observation of the world (consider, for example, Plato’s Symposia or Aristotle’s Rhetoric) and because learners were also expected to translate that learning back into service of the community through their practice of the discipline and through their continued integration as the next generation of guides or teachers. This made for a kind of non-hierarchical equivalency that characterized the period: learners were simply future teachers, and learning was just one stage in a continuous system. The direct connections between learners and teachers and between learning and service (even if that service was for a profit) meant that learning was, in Baudrillardian terms, a “reflection of a profound reality” (6), creating a symbolic understanding of learning we might call “sacramental.”

2nd-order learning: The dawn of early industrial culture not only transformed how we produced goods but also how we “produced” learners, and the focus of learning increasingly became dominated by the factory. Not only did we shift the structure of schools better to match that of the factory (with layers of “management,” regularized hours, etc.) but we also increasingly expected the “products” of education — and even the overall goals of education — to take on the nature of factory productions: reproducible, measurable, standardized, and broken down into easily manageable and discrete pieces. The increasing call for universal education in the 18th and 19th centuries, although deriving from certain high-minded concerns about human potential, were equally focused on producing a functional and docile workforce — a “raw material” that was just as essential as iron, cotton, and wood to early factories. Although education still sought to prepare learners in the fields of study that had developed in the first stage, second-order learning increasingly separated the activities of learning from activities associated with making in real-world contexts. Instead, second-order learning replaced them with repetitive, hermetic tasks focused on building discipline and obedience. Indeed, the crowning representation of this new focus on control, paraded and parodied in countless retellings, was a school-bell system that mirrored the factory’s whistle — chiming out an end to students’ “shifts” of drudging work in precisely the same way their parents were freed from their factories. Although the new model of learning seemingly adopted the overall substance of first-order learning, it thus used that substance for largely opposite purposes: holistic, individualized empowerment was, for most participants, replaced by delimited, standardized systems of control and subjugation. Although certain elite learners were still able to operate according to the old system (access typically being limited based on class or financial capability), the new system of the second phase sought to replace it with something more “rational.” The idiosyncratic, learner-centric model of the old system was seen as an inefficient and anachronistic hold-over, and second-order educators sought to replace it with standardized materials, standardized curricula, and standardized progress that would unlock the efficiencies necessary to establish universal education. In so doing, corners had to be cut, the craft of teaching was increasingly replaced with rationalized and standardized “science,” and the careful attention to individual learning needs had to be abandoned. What had been a communal equivalency between learners and teachers became increasingly stratified and hierachized for most participants. Although many more students could be processed through the new school “factories,” the symbolic meaning of education as a signifier was progressively diluted — a product of increasing standardization, disentanglement from real-world contexts, and the use of education as a system of control. In this second phase, the symbolic significance of learning thus begins to “mask[…] and denature[…] a profound reality” (Baudrillard 6).

3rd-order learning: By this third stage, the notion of universal education — and the system of rationalization and standardization it required — was becoming so dominant and so conventional that it had largely displaced the notion of individualization that once characterized education. Indeed, the embrace of standardized learning and standardized testing transformed the entire educational enterprise. Politicians and educators alike touted the triumph of rationalizing “educational outputs,” fueled in part by the introduction of technologies like the IBM 805 Test Scoring Machine in 1937. In this context, schools proved their worth not primarily by how they engaged students in meaningful enterprises but rather by students’ scores on a range of standardized tests developed and honed over decades. As this period progressed, the pursuit of increasing performance metrics drove a relentless focus on “efficacy,” “efficiency,” and “results.” Coupled with economic and cultural pressures, this move to “industrialize” led to a narrowing of disciplinary offerings and a streamlining of curricula in the disciplines that remained. The focus on “evidence” led to a predictable preference for disciplines dominated by discrete, rational information — science and math — and an increasing marginalization of the “fluffy” disciplines associated with the humanities — music, art, literature, and languages. Disciplines were adapted to accommodate only those characteristics that testing could measure and that administrators and legislators wanted. The world of third-order learning was thus filled with activities whose every characteristic and rationale were already shaped by their ability to prove the value of standardized assessment. What had begun as an effort to serve ever larger numbers of students through a rational system of metrics in the second phase thus became in the third an end in itself. Teachers, students, and schools were evaluated based on their ability to meet standards in an increasingly proscribed way, and economic, social, and legislative efforts enforced compliance. At the same time, the work of schools became even further disconnected from active substantiation in the real world. While a sort of lip-service was still paid to the ways learning would benefit students “after graduation,” the notion of actual application was increasingly marginalized, reserved for “vocational learning.” Such learning of trades was also increasingly discredited, seen as an option only for those who couldn’t make it in “real” school — which, ironically, was increasingly characterized by its divorce from the real. The net effect was a separation of the signifiers of education (grades, degrees, and measurements of performance) from what they had once signified (holistic expertise and application). Isolated from opportunities for engagement in real-world contexts or activities, students were increasingly channeled to embrace a model of “academic achievement” whose primary task involved serving the assessment regimen. This shift is perhaps best epitomized in the increasing focus on test preparation as a dominant part of primary and secondary school curricula. Students, in turn, realizing what was actually at the heart of the system, also began to prefer the signifier over its signified, pursuing the grade (rather than the learning it was meant to certify) as a way of gaming the academic system: “I really need an A in this class so I can get into the college I want” (or “keep my scholarship” or “get that job” or any number of possibilities). Such displacement shows a kind of triumph of “marketing” that almost completely severs the tenuous relationship between reality and signification. In fact, this endless echo-effect became so pervasive that people begin to lose touch with what “real” learning even meant — at least in first-order terms. The closest most people got was the ghost of past academic rituals that still haunted academic proceedings in the form of nostalgia — parades of academic regalia and increasingly hollow references to the “rights, privileges, and responsibilities hereunto appertaining” on diplomas. Those rituals, originally designed to mark participants with the outward signifiers that pointed to an attainment of expertise through the investment of time and work, now became largely boundary marking events. Those outside of the academic system expected to have to train graduates thoroughly in “real work” because the application of skills was almost entirely missing from their educational experience. We might therefore call this third phase “the order of sorcery” because the symbolic accoutrements of learning only “play[ed] at being an appearance” (Baudrillard 6) — seeking to comfort us with a reassuring “reality” that proved itself almost entirely illusory if we peeked behind the curtain. Backed by carefully measured yet largely meaningless piles of standardized data, educational attainment in this third phase therefore covered over the fact that there was little real behind those scores because their chief function was to “mask[…] the absence of a profound reality” (6).

4th-order learning: For many schools (especially in the US), the confluence of standardized testing, “results”-based funding, international competition, the productization of education for business purposes, and political opportunism turned the nature of education on its head in this final phase. In what we might call the “simulacrum” of learning, schools’ dependency on student test scores for survival and funding made students not the beneficiaries but rather the fodder of a hermetic bureaucratic system no longer centrally focused on their holistic preparation. Second- and third-order efforts to assess and guarantee school performance according to standardized outcomes fully metastasized, resulting in a system so disconnected from the real that it was virtually unrecognizable. A few giant multinationals now controlled not only the standardized exams and all of the preparatory materials that supported them, but also entire curricular catalogues, their chief aim being to lock educational entities fully into their resource monopolies, maximizing profit by controlling the entire educational project (consider the case of the Canuttllo school district, near El Paso). Schools, under pressure to meet performance metrics or be punished, not only scrubbed from their rolls “undesirable” students who might bring down test scores, but also “juked the stats,” manipulating performance in ways that sometimes included outright cheating (Atlanta and Houston being just two notable instances). School curricula were perverted to serve particular, narrow political ideologies (consider the recent dustup over Texas’ treatment of slavery or its rewriting of textbooks). In the fun-house hall of mirrors that resulted, there was one glaring absence: concern with increasing capabilities that benefitted learners. Despite a relentless focus on improving test scores, those test results had nothing to do with creativity, innovation, or entrepreneurship as Yong Zhao has recently shown with PISA scores here and here. Educational enterprises are designed to compete with one another, but are utterly divorced from what people once considered reality — that connection to developing human capability and expertise through real-world application. This is the world of the “hyperreal,” a world

“produced from [….] models of control [that] no longer needs to be rational, because it no longer measures itself against either an ideal or negative instance. It is no longer anything but operational. In fact, it is no longer really the real […]” ( Baudrillard 2).

In this phase, the image “has no relation to any reality whatsoever; it is its own pure simulacrum” (6).

Of course, what I’m describing here — like Baudrillard was doing — are overall superstructures, the symbolic frameworks that give shape and meaning to our world and the way we read it. It’s not that good, caring teachers have disappeared in the fourth order, nor have instances of applications of real-world learning to real-world situations (for example, efforts in problem- and challenge-based learning). And this is not to say that students can’t learn and benefit, even if their educational lives are dominated by fourth-order structures. However, the existence of a fourth-order “simulation” means that teachers who want to operate according to a different model must fight an entire symbolic system arrayed against them, and they must invent a new kind of language — a new form of signification — to succeed.

In our next installment, we’ll begin exploring what that system of signification might look like and what it might mean for us to move beyond the fourth order. I hope you’ll join me…

September 13, 2016 at 9:15 am

Thank you William for writing this… Still thinking through it… as a biz, marketer/sales guy that values human centered learning/context, I would of course take issue with the thought that ‘Product backgrounds and spokespeople are fabricated to fit given market segments.’ Even though that statement holds true for many reasons, it didn’t take away the deepest desire which drew me to this task in the first place, and that is to influence the world of technology in a way that makes it come out to us, into our ‘real’ world, to where we at least use our hands to help create and make meaning.

I really like this, but had to stop at 1st order learning and get back to work 🙂 oh the shame… I’ll come back as I want to finish. Thanks you. (Don Orth posted to LinkedIn, glad he did or I wouldn’t have seen it.)

Stephen Moore

Director of Education ‘Development’ 🙂

Osmo

LikeLike